Growing Through the Cracks : Urban Farming in Sunnyside

- CDRC

- Sep 30, 2021

- 4 min read

By : Susan Rogers and Ariana Flick

Houston’s urban landscape is often categorized by its vast amount of open land. Partner this landscape with a history of agriculture and it seems hard to imagine that many Houstonians live without access to fresh foods. In 2012, a study by The Food Trust found that Houston had fewer supermarkets per capita than most major cities. Today, this is still the case, and particularly true for low-income communities. Much of Sunnyside, a historic African American community, is considered to be a food desert. In place of grocery stores, there is an abundance of fast food and convenience stores. Given that many residents lack access to a vehicle, healthier options are often out of reach.

A food desert, according to the Food Conservation and Energy Act passed by Congress in 2008, is an “area with limited access to affordable and nutritious food, particularly located in lower income neighborhoods.” Three data points define food deserts: (1) Accessibility to sources of healthy food, as measured by distance to a store or by the number of stores in an area; (2) Individual-level resources that may affect accessibility, such as family income or vehicle availability; and (3) Neighborhood-level indicators of resources, such as the average income of the neighborhood and the availability of public transportation. Yet, this metric fails to capture the quality of foods available at grocery stores in low-income neighborhoods, and the cost.

A recent study by the University of Houston headed by Sujata Sirsat found alarming spikes in bacteria found in produce available at grocery stores in low-income versus high-income areas stating it is, “essentially telling people in low income areas that it’s safer to eat processed foods and risk long-term chronic health conditions rather than eating fresh produce.” The discrepancies in food quality could be due to a multitude of factors: poor store management, supply chain problems, or inadequate personal hygiene.

Urban farming across Houston is expanding, and many farmers are working to address access to healthy food, including in Sunnyside. One of these farmers Ivy Walls of Ivy Leaf Farms. Starting with a garden in her backyard in 2019, Ivy has now expanded into a full farming operation with plant pop ups, gardening classes, the Black Farmer Box distributions, a mobile GreenHOUwse, and so much more; but, she is not alone. Fresh Life Organic, Hope Farms, Plant it Forward, Finca Tres Robles, Bonham Acres, and LBJ Farm are all urban farming ventures that have taken off in the past ten years with the intent of serving food deserts such as Sunnyside while also increasing access to locally grown foods and employment opportunities.

Many young farmers are emerging black entrepreneurs, returning to their communities and investing locally with a social justice mission. In this spirit, Jeremy Peaches of Fresh Life Organic and Ivy Walls started the Black Farmer Box program with a mission to create a sustainable, equitable, and affordable food system for fto food desert communities. The seasonal boxes are stocked with locally grown produce supporting both growers and those in need of healthy food.

In the fall of 2020, Professor Susan Rogers and her undergraduate architecture studio partnered with Ivy Walls to develop concepts for Ivy Leaf Farms in the form of a grocery store, community center, and garden on the intersection of Holmes Road and Scott Street. The goal was to test ideas and explore models for a comprehensive urban farming program that included places for community members to gather and spaces to teach about and grow fresh foods. Three student proposals illustrate the strength of this concept.

Alex Asaud’s project focuses on this idea of creating a billboard and iconography in Sunnyside. Most of the program lies on the first level of the project with an elevated park space and greenhouse above. Lifting the greenhouse and park space allows the project to be seen from 610, a heavily trafficked freeway, and would be an advertisement to bring visitors from outside of the community.

In this project by Melanie Getman, the idea of creating a community social space is the main driver. By cutting a pathway through the site that can be barricaded off for events, the project creates a promenade. This central space could be used for festivals, farmer’s markets, or community fairs.

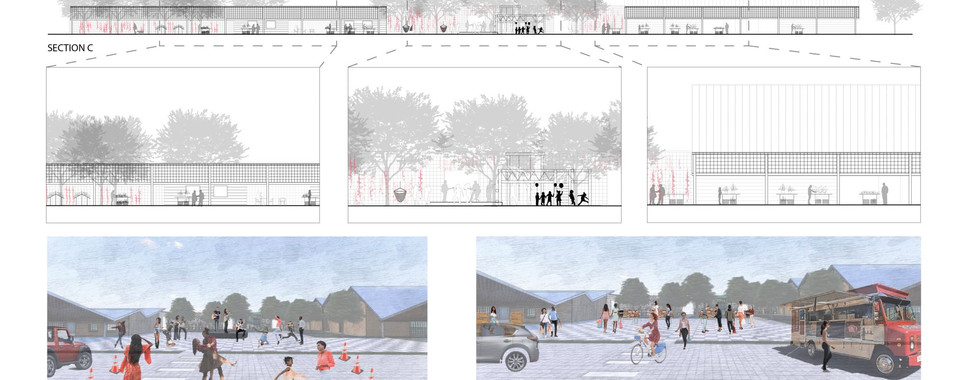

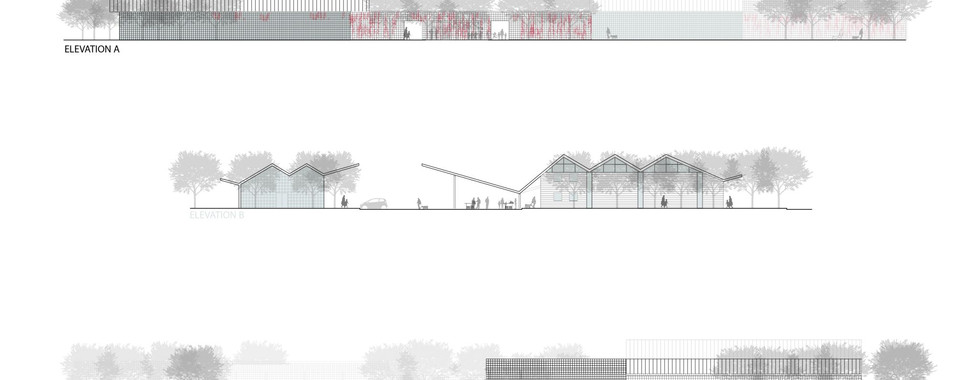

The final project, by Ariana Flick, focuses on the idea of creating a productive landscape. Sectioned by the pathways, every open space is meant to be programmed and used for the production of food or used for events. The building is isolated to the eastern edge of the site as a landmark for those coming from 610.

Urban farming programs bring community members together, support growers and entrepreneurs, and make healthy foods more accessible. Recently, Ivy Walls and Jeremy Peaches announced that their next goal will be to open a grocery store of local produce within Sunnyside. Ivy Walls believes that everyone deserves to eat fresh and healthy foods and this project will bring that mission full circle, making the healthy choice the easy choice.

Academic success requires well-crafted assignments that meet university standards. With Assignment Help Online, you gain access to top-tier writers who deliver plagiarism-free content. Whether it’s editing or full drafting, expert assistance is just a click away. Don’t wait—try Assignment Help Online today and experience stress-free submissions!

Learners often speak highly of how well-rounded the courses at the College of Contract Management are. Each course not only covers technical knowledge but also focuses on practical skills that are immediately applicable. Students find themselves using course content in their day-to-day roles. This leads to faster growth and better job performance. The courses are more than theoretical—they’re transformational. That’s a major win for any professional.

This was such a refreshing read. It’s amazing to see how something like urban farming can take root literally and figuratively in spaces that were once overlooked. It really makes me think about how healing comes in many forms, whether it's through nature, food or even body care. In my own life, finding balance through practices like massage therapy in Prescott, AZ has helped me reconnect with my health in a grounded intentional way. Beautiful work being done in Sunnyside thank you for sharing this.

Urban farming initiatives like Ivy Leaf Farms and the Black Farmer Box program in Sunnyside not only address food deserts but also exemplify how community driven efforts can foster resilience and sustainability. These projects remind me of the importance of tailored support systems in various fields. Just as these farmers provide essential resources to their communities seeking a marketing assignment service can offer students the guidance they need to navigate complex concepts effectively.

Finding reliable Psychology Dissertation Help can be a game-changer for students struggling with complex research topics, literature reviews, or data analysis. Many psychology students often face issues when selecting an appropriate methodology or structuring their dissertations properly. That's where professional dissertation assistance comes in. From topic selection to proofreading the final draft, expert writers ensure that your dissertation meets academic standards and guidelines. Whether you're dealing with clinical psychology, cognitive behavior, or developmental theories, tailored support can really boost your confidence and academic performance. If you're aiming for high grades or want to impress your supervisor, consider opting for Psychology Dissertation Help from experienced professionals who understand university expectations and can guide you step by step through the dissertation writing journey.